Parisian Art Movements Through the Ages: From Baroque to Impressionism

Paris has long been regarded as the beating heart of European art.

From its heavily decorated churches, adorned with dramatic frescoes to the cafés where artists once gathered, the city has shaped, nurtured, and transformed artistic expression for centuries.

Walking through Paris today, you’ll see the legacy of its art movements everywhere: in the architecture, in its famous museums, and in the streets that once hosted revolutionary ideas.

In this article, we’ll take a journey through Parisian art history, following the progression of styles from the iconic Baroque period to the brilliance of Impressionism.

This timeline will give you the tools to better appreciate the masterpieces you’ll encounter in your visit to Paris.

The Baroque Period in Paris (17th Century)

Baroque art swept through Europe in the early 17th century, and Paris embraced it with its own distinctive flair.

While Rome and Madrid are often remembered as the great Baroque capitals, France, and Paris in particular, adapted the style in ways that reflected its growing political and cultural power.

Baroque art is characterized by the colorful scenes, exuberant detail, movement, and grandeur.

Think of swirling draperies, intense contrasts of light and dark, and theatrical compositions designed to amaze.

In Paris, the Baroque became a tool of both the monarchy and the Church, intended to display authority, wealth, and divine order.

Key Figures

• Simon Vouet: Often credited with introducing Baroque style to France after studying in Italy. His works blended dramatic Italian influences with a more refined French sensibility.

• Charles Le Brun: Perhaps the most important Baroque painter in Paris. As the official painter of King Louis XIV, Le Brun oversaw the decoration of Versailles and set the tone for French art of the era.

Where to See It

The Baroque style flourished in Parisian churches and royal commissions.

Visitors can admire this grandeur at Église Saint-Sulpice, which features monumental Baroque decoration, and at the Palace of Versailles, just outside Paris, where Le Brun’s works are displayed in all their splendor.

The Rococo Movement (18th Century)

If the Baroque was about drama and grandeur, Rococo was about intimacy, elegance, and pleasure.

Emerging in the early 18th century, Rococo art reflected the lighter, more playful atmosphere of Parisian high society before the turbulence of the French Revolution.

Rococo art is ornate, whimsical, and delicate.

Pastel colors, soft lines, and scenes of leisure, love, and nature dominate the style.

Unlike the Baroque’s emphasis on power and divinity, Rococo celebrated everyday pleasures and romantic escapades.

Key Figures

• Jean-Antoine Watteau: Considered the father of Rococo painting, Watteau’s works, such as Pilgrimage to Cythera, epitomize the dreamy, romantic quality of the style.

• François Boucher: A favorite of Madame de Pompadour, mistress of Louis XV, Boucher painted idyllic, sensual scenes that perfectly embodied Rococo elegance.

• Jean-Honoré Fragonard: Known for his playful and often suggestive paintings, such as The Swing, Fragonard captured the frivolity of Parisian aristocracy.

Where to See It

The Louvre Museum houses iconic Rococo works by Boucher and Fragonard.

For a more immersive experience, the Musée Cognacq-Jay in the Marais showcases 18th-century Parisian art in a mansion setting that feels true to the period.

Neoclassicism (Late 18th to Early 19th Century)

By the late 18th century, the frivolous elegance of Rococo began to feel out of step with the times.

As political unrest grew and the Enlightenment spread new ideals, artists turned to the ancient world for inspiration.

Thus, Neoclassicism emerged in Paris, emphasizing order, rationality, and moral virtue.

Neoclassicism was marked by clarity, symmetry, and an emphasis on classical themes from ancient Greece and Rome.

Strong lines replaced Rococo’s softness, and heroic, moralizing subjects replaced playful romance.

Key Figures

• Jacques-Louis David: The undisputed master of Neoclassicism, David’s works, such as The Oath of the Horatii and The Death of Socrates, reflected the ideals of sacrifice and civic duty. During the French Revolution, his art became political propaganda.

• Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres: A student of David, Ingres combined classical precision with sensuality, producing works like La Grande Odalisque, which hinted at Romantic influences to come.

Where to See It

The Louvre is the best place to admire Neoclassical masterpieces, particularly the grand canvases of Jacques-Louis David.

The Musée Ingres Bourdelle (in Montauban, though worth noting for travelers in France) is dedicated to Ingres’ legacy.

Romanticism (Early to Mid-19th Century)

If Neoclassicism reflected reason and discipline, Romanticism celebrated passion, emotion, and imagination.

In Paris, Romanticism flourished in the early 19th century as artists rejected the strict rules of Neoclassicism and embraced individuality.

Romantic art is expressive, dramatic, and often focuses on themes of nature, heroism, and exoticism.

It was about feeling, not logic, capturing the sublime and the emotional extremes of human experience.

Key Figures

• Eugène Delacroix: The leading Romantic painter in Paris, Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People remains one of the most iconic images of both Romanticism and French identity.

• Théodore Géricault: Best known for The Raft of the Medusa, Géricault’s dramatic compositions conveyed the chaos and vulnerability of human life.

Where to See It

The Louvre displays Delacroix’s and Géricault’s monumental canvases, while the Musée Delacroix in the artist’s former home offers a more intimate perspective on his work.

Realism (Mid-19th Century)

As the 19th century progressed, artists in Paris once again turned to new ideas.

Following the 1848 Revolution, a movement emerged that rejected both Romantic idealization and Neoclassical heroism.

Instead, Realism sought to depict life exactly as it was, often highlighting the struggles of ordinary people.

Realism is characterized by unembellished, truthful depictions of contemporary life.

Farmers, laborers, and everyday scenes became central subjects, painted with honesty and sometimes unflinching detail.

Key Figures

• Gustave Courbet: Considered the father of Realism, Courbet’s The Stone Breakers and A Burial at Ornans shocked audiences by treating common people with the same dignity as historical or religious figures.

• Jean-François Millet: While based more in the countryside, Millet’s works, like The Gleaners, influenced Parisian art circles with their sympathetic portrayals of peasant life.

Where to See It

Courbet’s works can be seen in the Musée d’Orsay, which holds one of the most important collections of 19th-century French art.

Impressionism (Late 19th Century)

No movement is more closely tied to Paris than Impressionism.

Born in the cafés and studios of the city in the 1870s, Impressionism revolutionized not just French art but the entire course of Western painting.

Impressionism was all about capturing fleeting moments, the impression of light, color, and atmosphere.

Artists painted quickly, often outdoors (en plein air), using visible brushstrokes and vibrant colors.

Subjects ranged from Parisian boulevards to suburban landscapes and modern leisure activities.

Key Figures

• Claude Monet: Known for works like Impression, Sunrise (from which the movement takes its name), Monet focused on light and atmosphere, painting the same scene at different times of day.

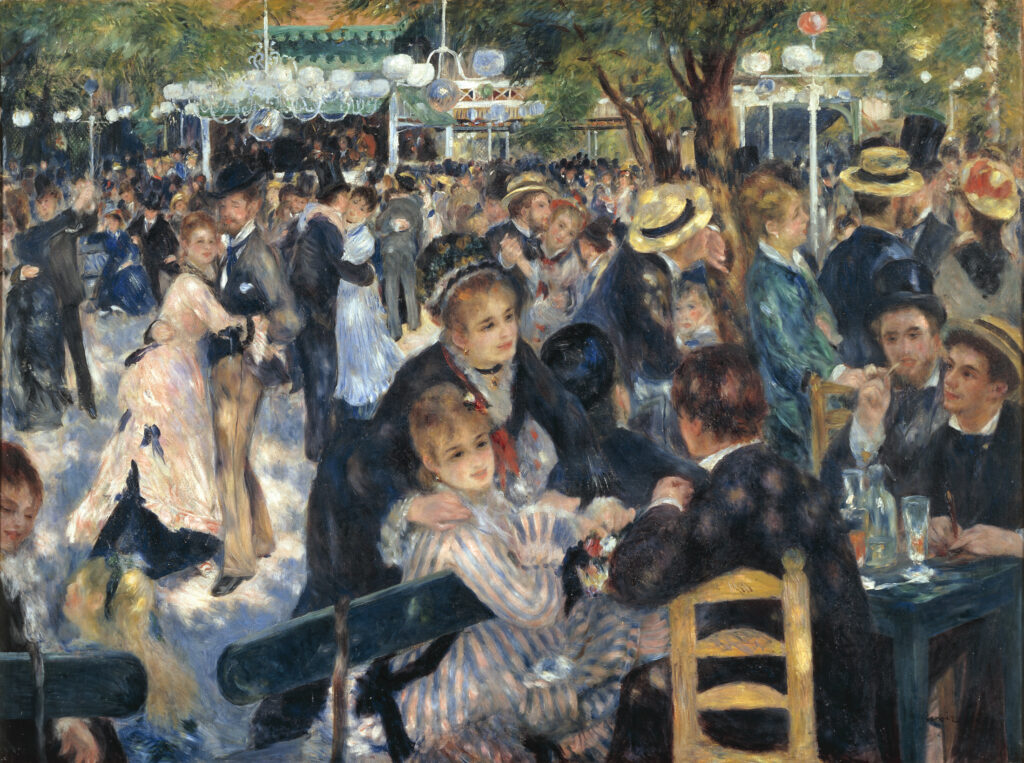

• Pierre-Auguste Renoir: Renoir’s joyful depictions of Parisian life, such as Dance at Le Moulin de la Galette, capture the spirit of the Belle Époque.

• Edgar Degas: While often grouped with the Impressionists, Degas focused on movement and modern urban life, particularly through his famous ballerina paintings.

• Camille Pissarro: Sometimes called the “dean of the Impressionists,” Pissarro played a crucial role in organizing the group and painting both urban and rural scenes.

Where to See It

The Musée d’Orsay is the ultimate destination for Impressionism, with galleries dedicated to Monet, Renoir, Degas, and more.

The Musée de l’Orangerie houses Monet’s breathtaking Water Lilies, while the Musée Marmottan Monet offers the largest collection of Monet’s works in the world.

Final Thoughts

For art lovers, Paris is a living museum.

Its streets, churches, and galleries tell the story of how creativity transformed over centuries, reflecting the city’s shifting politics, philosophies, and lifestyles, with each movement growing in dialogue with its predecessor: Rococo lightness following Baroque drama, Neoclassical order answering Rococo frivolity, Romantic passion reacting against Neoclassical restraint, Realism challenging Romantic exaggeration, and Impressionism breaking free from the constraints of academic painting.

This chain of reactions shaped not just Parisian art but the broader trajectory of Western art history.

Parisian art movements are not just about style; they are about the human experience, captured and reimagined through brushstrokes that continue to inspire the world.